随着耐碳青霉烯类肺炎克雷伯菌(carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, CRKP)检出率不断上升[1-2],其已成为全球优先预防与控制的耐药菌之一[3],并为临床治疗和医院感染预防与控制带来巨大挑战。研究[4]显示,医疗机构内CRKP的定植/感染常通过接触传播,以医务人员、患者、共用的医疗设备及病区环境为媒介造成交叉传播,有抗菌药物使用史、接受侵入性操作和外科手术、入住重症监护病房(ICU)及免疫功能低下的患者是感染的高风险人群[5-6]。在我国,CRKP造成的医院感染多报道于ICU、神经内科和新生儿病房[7-9]。血液肿瘤患者作为CRKP感染的高危人群,预防与控制感染的发生,降低其感染和病死率对临床具有重要意义[10-11]。本研究就某教学医院成人血液肿瘤科2022年6月CRKP感染疑似暴发事件进行流行病学调查、环境卫生学监测,并分析感染的高危因素,采取一系列干预措施,最终得到有效控制。本研究旨在为血液系统疾病患者CRKP医院感染的预防与控制提供参考。

1 对象与方法 1.1 研究对象2022年6月10—30日某教学医院成人血液肿瘤科血标本检出CRKP的6例血液肿瘤科患者及同期入院的其他患者,共464例。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 流行病学调查及应急处置依据《医院感染暴发与控制指南》(WS/T 524—2016)[12]和《医院感染诊断标准(试行)》(2001年)[13]中关于败血症的判定,参照现场调查表及事件控制程序实施应急处置,即病例判定和诊断核实。

1.2.2 指标计算医院感染罹患率=短时间内科室医院感染的患者数/同期在科患者数×100%;CRKP医院感染罹患率=短时间内科室CRKP感染患者数/同期在科患者数×100%。

1.2.3 环境目标菌监测依据美国疾病控制与预防中心(CDC)2010年《环境清洁评价方法》[14]中关于高频接触位点的定义,将本次事件环境监测位点分为3部分:(1)患者部分,包括床栏、床头柜、输液架、呼叫铃等;(2)卫生间区域,含水槽、灯开关、门把手等;(3)公共区域,含监护仪表面、B超机操作面板、空调开关等。调查小组分别于终末消毒前(6月28日)及终末消毒后(7月2日)对上述点位进行现场采样。采样方法为使用浸有生理盐水的无菌纤维拭子对物体表面进行最大面积涂抹,现场接种于血营养琼脂培养基上,立即送微生物实验室进行细菌培养和鉴定。菌落数卫生标准参照《医院消毒卫生标准》中Ⅱ类环境要求(≤5.0 CFU/cm2)。

1.2.4 病原学鉴定及药敏试验使用VITEK MS全自动微生物分析系统和Clin-To F-Ⅱ飞行时间质谱仪进行菌株鉴定,VITEK 2全自动微生物分析系统和K-B纸片扩散法进行药敏试验,按标准进行结果判读[15]。

1.2.5 同源性分析将仅留存的检出CRKP的2例患者血标本与环境CRKP检测阳性标本外送第三方生工生物工程(上海)有限公司进行16s RNA及多位点序列分型(MLST)测序,分析其同源性。16s RNA分析网站:https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi;MLST分析网站:https://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/klebsiella/。

1.3 统计分析应用SPSS 27.0统计软件进行数据分析。检验资料是否符合正态分布采用P-P图,计量资料比较采用t检验或秩和检验,计数资料比较采用卡方检验或Fisher确切概率法。P≤0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 疑似医院感染暴发判定2022年6月10—30日CRKP导致的医院获得性血流感染罹患率为1.29%(6/464),较2021年同期(0,0/513)高,差异有统计学意义(P=0.011)。核实为一起CRKP血流感染疑似医院感染暴发事件。

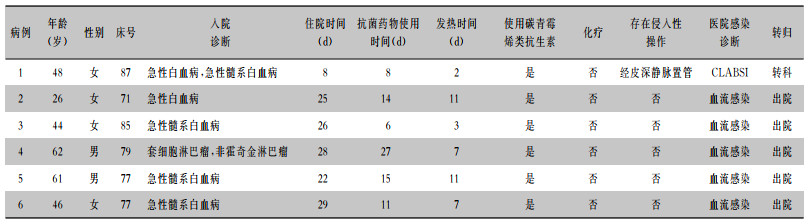

2.2 流行病学调查 2.2.1 人群分布本事件中感染患者血培养检出的CRKP,经药敏试验结果提示耐药表型完全一致,仅对替加环素、黏菌素敏感。6例患者中,女性4例(66.67%),男性2例(33.33%);平均年龄中位数47岁;血液科住院时间中位数25 d。患者住院期间均出现发热,6例患者均使用过碳青霉烯类抗生素,本次在院期间未进行化学治疗(化疗);1例转科,其余5例均留院治疗。6例患者中,1例患者存在中心静脉置管,医院感染诊断为中心静脉导管相关血流感染(CLABSI),5例医院感染感染诊断为非CLABSI血流感染,见表 1。

| 表 1 6例CRKP医院感染患者基本特征 Table 1 Basic characteristics of 6 patients with CRKP HAI |

|

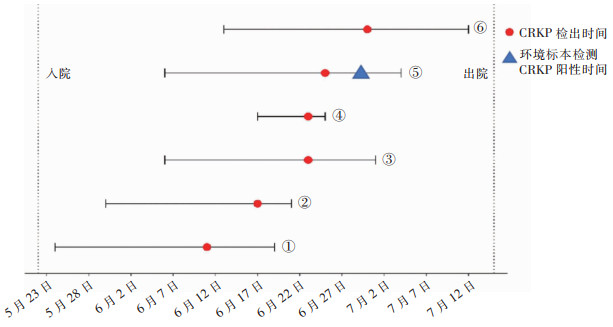

2022年6月11日微生物实验室报告首例血培养检出CRKP患者,此后6月17、25、30日各有1例患者血标本检出同种病原菌,23日检出2例。患者住院及病例微生物标本培养CRKP分布见图 1。

|

| 图 1 6例CRKP血流医院感染病例及环境CRKP分离标本时间分布图 Figure 1 Time distribution of isolation of CRKP from 6 patients with CRKP HA-BSI and CRKP from environmental specimens |

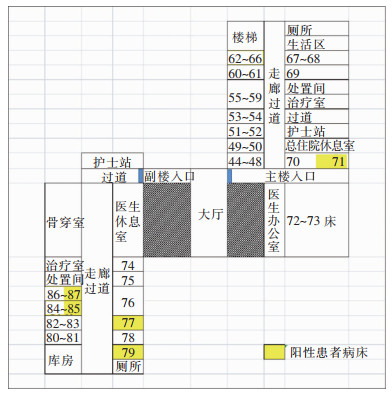

6例患者中有5例分布在病房同一区域,且有2例患者住过同一病床(77床)。医生、护士在病区诊疗环境中存在交叉,同一层楼仅1名保洁人员。见图 2。

|

| 图 2 6例CRKP血流医院感染患者空间分布图 Figure 2 Spatial distribution of 6 patients with CRKP HA-BSI |

终末消毒前共采样44份,仅1份标本检测结果合格,合格率为2.27%。44份标本中医务人员手标本16份(36.36%),物体表面28份(63.64%)。结果显示,42份(95.45%)标本菌落计数均为无法计数,但仅1份(2.27%)标本检出CRKP,为79床层流床床帘,其药敏结果与患者检出的CRKP药敏结果基本一致。终末消毒后采样45份(均为物体表面),31份标本检测结果合格,合格率为68.89%。45份标本中2份(4.44%)无法计数,12份(26.67%)菌落可计数,且>5 CFU/cm2。终末消毒后该病区环境菌落计数合格率高于消毒前,差异有统计学意义(χ2=42.392,P<0.001)。

2.4 CRKP同源性分析将病例5、6血标本检出的CRKP菌株与环境标本检出的CRKP菌株进行同源性分析,结果显示3株CRKP的16s RNA完全相同,相似度100%;3株CRKP的7个管家基因均相同,都属于ST11型。即CRKP临床株与环境株高度同源。

2.5 控制措施及效果共开展6项集束化控制措施。第一阶段:医院感染管理专职人员接到微生物实验室报告的第1例血标本CRKP预警后,立即指导病区对检出CRKP的患者进行集中安置,并现场指导床单元终末消毒。第二阶段:强化阶段,即6月28日再次接到检出报告后,除了持续落实前期2项措施外,额外要求增加4项措施,即强化医务人员手卫生,适当关闭病区,限制本病区医务人员流动(即不与其他病区交叉),固定责任医生及护士策略。其中,适当关闭病区指同一楼层左右两个病区按终末消毒程序前后依序关闭。其次,建议采取主动肛拭子筛查的形式对潜在的CRKP定植或感染患者进行预防性隔离。此外,根据环境目标菌检测结果对终末消毒策略进行4步强化,包括:(1)由经过医院感染管理专职人员培训后的本病区护理人员替代保洁人员进行终末消毒;(2)使用过氧化氢喷雾分3次进行空气消毒;(3)更换不便于清洁消毒的床垫、被褥;(4)加强空调出风口、公用设备等物体表面清洁消毒。采取以上措施后,随后一个月内(7月1—30日)无新检出的CRKP医院感染病例。

3 讨论研究[16]指出,不同的碳青霉烯酶所需要使用的治疗药物不同,随着肺炎克雷伯菌耐药基因的不断变化,可选择药物不断减少[17-18],预防与控制CRKP的产生及传播成为临床和感染防控工作迫切需要关注的问题。2项Meta分析研究[19-20]显示,患者合并CRKP感染时其病死率为33%(95%CI:28%~38%)、42%(95%CI:37%~47%),而血液肿瘤患者因化学治疗导致中性粒细胞降低或缺乏、长期使用免疫抑制剂等,使耐碳青霉烯类肠杆菌(CRE)血流感染后30天病死率高达51%[21]。研究[22]证实及时采取消毒隔离,提高医务人员手卫生依从性,加强环境物体表面清洁消毒等基础感染控制措施后,能够使CRKP医院内传播得到有效控制,但国内外措施存在一定差异。随着近年来微生物检测技术在医院感染防控领域中的广泛应用,在血液肿瘤患者中开展CRE主动筛查和加强抗菌药物管理作为强烈推荐证据成为医院感染防控的新措施,已在中国学者中达成共识[23-24]。

本研究中成人血液科在20 d内出现6例CRKP血流感染患者并初步判定为疑似医院感染暴发。6例CRKP血流感染患者年龄中位数为47岁,均联用抗菌药物,住院日数中位数为25 d,高于未感染组,与相关研究[25-26]对CRKP医院感染危险因素分析的结果相符。本研究中CRKP感染患者未出现死亡病例,虽然与2019年一项抗菌药物耐药性负担研究预测的高病死率结论有差异[26],但究其原因,除了本次感染病例入院期间均未进行化疗、侵入性操作且感染均得到及时治疗外,不排除与耐药革兰阴性菌较革兰阳性菌所导致血流感染患者病死率更低有关[27]。在本次事件传染源及传播途径的假设和验证中,发现最后2例CRKP感染患者的临床菌株与6月28日环境标本中检出的CRKP高度同源,虽然不能验证两者之间污染和被污染的因果关系,但反映了此次暴发事件存在CRKP通过患者床单元环境在病区传播的可能,层流床床帘外表面的清洁消毒工作不容忽视,尤其收治多重耐药菌感染患者时更应加强清洁消毒。

鉴于CRE感染导致的严重后果,世界卫生组织(WHO)等已针对CRE医院感染防控提出一系列集束化感染控制干预策略[2-3],包括针对患者开展定植/感染的主动筛查(肛/咽拭子),集中或单间预防性隔离患者,提高手卫生依从性,避免转院,环境清洁消毒,环境中CRE的定植和污染筛查,减少侵入性操作和患者去定植等。但与WHO建议不同,在中国专家共识中,患者CRE去定植、环境消毒并未纳入推荐措施[24]。这表明适用于中国血液肿瘤患者的CRE防控措施还有待探讨。本研究除借鉴上述措施外,还固定并相对限制本病区医务人员流动,并实施了“关闭病区”策略,这在一定程度上能最大限度控制暴发事态[28],在本次事件中快速、有效扼制了病区内CRKP的传播。

本研究也存在一定局限性。一是仅对部分发热患者进行肛拭子CRKP筛查,不能为本次调查提供分析依据。二是采取控制措施时,在病区使用过氧化氢喷雾进行终末消毒时消毒次数为3次,是否存在消毒剂过量使用及其对患者产生的潜在影响有待进一步论证。关于终末消毒措施,部分研究[28-30]认为多重耐药菌的防控不需提高消毒剂浓度,而是依靠增加清洁消毒频次来保证病原体能够被有效消除;也有研究[31-32]表示因表面消毒剂能有效抑制环境中的多重耐药菌,只要严格落实常规清洁消毒即可消除环境中的CRE;而血液肿瘤患者CRE感染的诊治与防控中国专家共识[24]也仅将环境清洁作为强推荐措施,未强调消毒的必要性。由此可见,该措施仍未有统一定论。三是“适当关闭病区”策略虽能控制感染传播速度,但其所带来的后果如医疗资源不能迅速补充,无疑也对医疗机构带来冲击[28],其使用指征基于病原体的传播方式和患者的基础情况,适用性有待探讨。四是未能保留所有患者的临床标本进行同源性分析,以进一步验证环境污染是本次事件发生主要原因的假设。

鉴于研究者所在部门无独立检验设备,故本研究委托第三方进行同源性基因鉴定,未能呈现分型结果;且采取的多模式防控措施与部分研究有差异,在后续研究中,将对血液科高危患者开展主动监测和筛查,寻找并控制感染高危因素,防止病原体在医疗机构,尤其是血液科等重点部门内传播。

利益冲突:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

| [1] |

Senchyna F, Gaur RL, Sandlund J, et al. Diversity of resistance mechanisms in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae at a health care system in Northern California, from 2013 to 2016[J]. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 2019, 93(3): 250-257. DOI:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2018.10.004 |

| [2] |

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the prevention and control of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in health care facilities[EB/OL]. (2017-11-01)[2023-07-10]. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241550178.

|

| [3] |

乔甫, 宗志勇. 世界卫生组织《医疗机构耐碳青霉烯的肠杆菌科细菌、铜绿假单胞菌和鲍曼不动杆菌防控指南》介绍[J]. 华西医学, 2018, 33(3): 259-263. Qiao F, Zong ZY. Interpretation of guidelines for the prevention and control of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in health care facilities[J]. West China Medical Journal, 2018, 33(3): 259-263. |

| [4] |

Jolivet S, Lolom I, Bailly S, et al. Impact of colonization pressure on acquisition of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales and meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in two intensive care units: a 19-year retrospective surveillance[J]. J Hosp Infect, 2020, 105(1): 10-16. DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2020.02.012 |

| [5] |

Fang LL, Xu HP, Ren XY, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and subsequent MALDI-TOF MS as a tool to cluster KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, a retrospective study[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2020, 10: 462. DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2020.00462 |

| [6] |

Qin XH, Wu S, Hao M, et al. The colonization of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: epidemiology, resistance mechanisms, and risk factors in patients admitted to intensive care units in China[J]. J Infect Dis, 2020, 221(Suppl 2): S206-S214. |

| [7] |

Gu DX, Dong N, Zheng ZW, et al. A fatal outbreak of ST11 carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Chinese hospital: a molecular epidemiological study[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2018, 18(1): 37-46. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30489-9 |

| [8] |

Zeng LY, Yang CR, Zhang JS, et al. An outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in an intensive care unit of a major teaching hospital in Chongqing, China[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2021, 11: 656070. DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2021.656070 |

| [9] |

韩颖, 赖晓全, 徐敏, 等. 神经内科ICU耐碳青霉烯类肺炎克雷伯菌感染疑似暴发调查与控制[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2023, 22(5): 569-573. Han Y, Lai XQ, Xu M, et al. Investigation and control on a suspected outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in the neurological intensive care unit[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2023, 22(5): 569-573. |

| [10] |

Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Singer M, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of infection among patients in intensive care units in 2017[J]. JAMA, 2020, 323(15): 1478-1487. DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.2717 |

| [11] |

安彦锦, 杨怀, 牟霞, 等. 基于倾向指数匹配的耐碳青霉烯类肺炎克雷伯菌医院感染的经济负担评价[J]. 中华医院感染学杂志, 2022, 32(9): 1410-1414. An YJ, Yang H, Mu X, et al. Evaluation of economic losses due to carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial infection based on propensity index matching[J]. Chinese Journal of Nosocomiology, 2022, 32(9): 1410-1414. |

| [12] |

中华人民共和国国家卫生计生委法规司. 关于发布《医院感染暴发控制指南》等两项推荐性卫生行业标准的通告: 国卫通〔2016〕11号[EB/OL]. (2016-09-12)[2023-07-10]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/fzs/s7852d/201609/f3fada81c1cb454b96d2d4391ba73e9a.shtml. National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China. Notice on the issuance of two recommended health industry standards, including the guidelines for the control of nosocomial infection outbreaks: Guoweitong[2016] No. 11[EB/OL]. (2016-09-12)[2023-07-10]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/fzs/s7852d/201609/f3fada81c1cb454b96d2d4391ba73e9a.shtml. |

| [13] |

中华人民共和国卫生部. 医院感染诊断标准(试行)[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2001, 81(5): 314-320. Ministry of Health of The People's Republic of China. Diagnostic criteria for nosocomial infections (proposed)[J]. National Medical Journal of China, 2001, 81(5): 314-320. |

| [14] |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Options for evaluating environmental cleaning[EB/OL]. (2010-12)[2023-07-10]. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/toolkits/evaluating-environmental-cleaning.html.

|

| [15] |

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing-30th edition[EB/OL]. [2023-07-10]. http://webstore.ansi.org/standards/clsi/clsim100ed30.

|

| [16] |

Wang Q, Wang XJ, Wang J, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: data from a longitudinal large-scale CRE study in China (2012-2016)[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2018, 67(suppl 2): S196-S205. |

| [17] |

Poirel L, Jayol A, Nordmann P. Polymyxins: antibacterial activity, susceptibility testing, and resistance mechanisms encoded by plasmids or chromosomes[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2017, 30(2): 557-596. DOI:10.1128/CMR.00064-16 |

| [18] |

Seifert H, Blondeau J, Dowzicky MJ. In vitro activity of tigecycline and comparators (2014-2016) among key WHO'priority pathogens' and longitudinal assessment (2004-2016) of antimicrobial resistance: a report from the T.E.S.T. study[J]. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2018, 52(4): 474-484. DOI:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.07.003 |

| [19] |

Agyeman AA, Bergen PJ, Rao GG, et al. A systematic review and Meta-analysis of treatment outcomes following antibiotic therapy among patients with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections[J]. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2020, 55(1): 105833. DOI:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.10.014 |

| [20] |

Xu LF, Sun XX, Ma XL. Systematic review and Meta-analysis of mortality of patients infected with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae[J]. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob, 2017, 16(1): 18. DOI:10.1186/s12941-017-0191-3 |

| [21] |

Satlin MJ, Cohen N, Ma KC, et al. Bacteremia due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in neutropenic patients with hematologic malignancies[J]. J Infect, 2016, 73(4): 336-345. DOI:10.1016/j.jinf.2016.07.002 |

| [22] |

Munoz-Price LS, Quinn JP. Deconstructing the infection control bundles for the containment of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae[J]. Curr Opin Infect Dis, 2013, 26(4): 378-387. DOI:10.1097/01.qco.0000431853.71500.77 |

| [23] |

Dai YQ, Meng TJ, Wang XL, et al. Validation and extrapolation of a multimodal infection prevention and control intervention on carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in an epidemic region: a historical control quasi-experimental study[J]. Front Med (Lausanne), 2021, 8: 692813. |

| [24] |

中国碳青霉烯耐药肠杆菌科细菌感染诊治与防控专家共识编写组, 中国医药教育协会感染疾病专业委员会, 中华医学会细菌感染与耐药防控专业委员会. 中国碳青霉烯耐药肠杆菌科细菌感染诊治与防控专家共识[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2021, 101(36): 2850-2860. Expert consensus compilation group on diagnosis, treatment and prevention of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae bacterial infections in China, Infectious Disease Professional Committee of China Medical Education Association, Professional Committee on Bacterial Infection and Drug Resistance Prevention and Control of the Chinese Medical Association. Expert consensus on diagnosis, treatment and prevention of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections in China[J]. National Medical Journal of China, 2021, 101(36): 2850-2860. |

| [25] |

Hauck C, Cober E, Richter SS, et al. Spectrum of excess mortality due to carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2016, 22(6): 513-519. |

| [26] |

陈娅, 陈鸿, 刘瑶, 等. 耐碳青霉烯类肺炎克雷伯菌医院感染的危险因素分析[J]. 中华医院感染学杂志, 2019, 29(8): 1131-1135. Chen Y, Chen H, Liu Y, et al. Risk factors for nosocomial infections with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae[J]. Chinese Journal of Nosocomiology, 2019, 29(8): 1131-1135. |

| [27] |

Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis[J]. Lancet, 2022, 399(10325): 629-655. |

| [28] |

Amanati A, Sajedianfard S, Khajeh S, et al. Bloodstream infections in adult patients with malignancy, epidemiology, microbiology, and risk factors associated with mortality and multi-drug resistance[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2021, 21(1): 636. |

| [29] |

Ocampo W, Geransar R, Clayden N, et al. Environmental scan of infection prevention and control practices for containment of hospital-acquired infectious disease outbreaks in acute care hospital settings across Canada[J]. Am J Infect Control, 2017, 45(10): 1116-1126. |

| [30] |

杨启文, 吴安华, 胡必杰, 等. 临床重要耐药菌感染传播防控策略专家共识[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2021, 20(1): 1-14. Yang QW, Wu AH, Hu BJ, et al. Expert consensus on strategies for the prevention and control of spread of clinically important antimicrobial-resistant organisms[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2021, 20(1): 1-14. |

| [31] |

黄勋, 邓子德, 倪语星, 等. 多重耐药菌医院感染预防与控制中国专家共识[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2015, 14(1): 1-9. Huang X, Deng ZD, Ni YX, et al. Chinese experts' consensus on prevention and control of multidrug resistance organism healthcare-associated infection[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2015, 14(1): 1-9. |

| [32] |

Reichel M, Schlicht A, Ostermeyer C, et al. Efficacy of surface disinfectant cleaners against emerging highly resistant Gram-negative bacteria[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2014, 14: 292. |