2019年新型冠状病毒感染(COVID-19)的暴发引发了一场全球危机,严重急性呼吸综合征冠状病毒2型(SARS-CoV-2)在人群中迅速蔓延,造成数亿人口感染,导致高发病率和病死率[1]。虽然大多数COVID-19患者一般表现为轻中度症状,自主消退,但仍有部分患者发展为重症肺炎、肺水肿、急性呼吸窘迫综合征或多器官功能衰竭,病死率较高[2]。新型冠状病毒肺炎是患者住院和死亡的常见原因。

系统性红斑狼疮(systemic lupus erythematosus, SLE)是一种常见的自身免疫性疾病,因免疫复合物沉积于自身组织,导致自身免疫级联反应,进而导致多系统受累。中国SLE患病率每年约30/10万~70/10万,发病率每年约8.57/10万,发病率居于世界第4位[3-4]。目前已有研究[5]表明,SLE患者发生COVID-19后住院或死亡的风险比普通人群高。因此早期判断SLE患者合并COVID-19后是否发生肺炎就显得至关重要。

胸部CT检查是判断SLE患者是否发生新型冠状病毒肺炎的有效手段[6],但胸部CT检查不便于开展大规模筛查,且存在交叉感染的情况[7],因此,能否挖掘一些廉价、便捷且易于大规模检测的生物标志物来判断SLE患者合并COVID-19后是否发生肺炎是目前亟待突破的难题。已有研究[8-9]表明,过度活跃的免疫反应会导致机体产生过度炎症,这是冠状病毒介导的肺损伤和全身病理反应的重要因素。宿主免疫很可能是新型冠状病毒肺炎进展和恶化的主要决定因素之一。而一些新型炎症标志物已被证明在新型冠状病毒肺炎感染诊断中有重要作用[10]。其中,C反应蛋白(CRP)水平、血液白细胞亚群(中性粒细胞、淋巴细胞和单核细胞) 以及由这些参数产生的炎症指数引起了极大的关注。这些免疫参数可以通过血常规快速获得,是一种常规和低成本技术[11-13]。但是这些指标受多种炎症情况的影响,因此在确定COVID-19患者是否发生肺炎时,哪些指标具有更好的诊断价值目前仍未明确。

本研究旨在探讨SLE患者合并COVID-19后发生肺炎的危险因素,为SLE患者合并COVID-19后的临床病情评估提供帮助,并为临床治疗策略提供更多的参考。

1 对象与方法 1.1 研究对象回顾性纳入2022年12月—2023年2月就诊于南昌大学第一附属医院的250例SLE合并COVID-19患者,根据《赫尔辛基宣言》进行,并已获得南昌大学第一附属医院伦理委员会批准,伦理批准号:IIT[2023]临伦审第045号。

1.2 纳入与排除标准纳入标准:(1)符合2019年EULAR/ACR系统性红斑狼疮诊断标准[14];(2)经实时逆转录聚合酶链式反应SARS-CoV-2核酸检测或经SARS-CoV-2抗原检测确诊的COVID-19患者;(3)年龄≥18岁;(4)具有所需的临床资料,且所有纳入患者均完善胸部CT检查。将入选患者根据胸部CT检查结果分为对照组和肺炎组。排除正在接受化学治疗、有活动性恶性肿瘤或有恶性血液病等可能影响血常规或CRP数值的患者。SLE患者病情活动度的评估采用SLEDAI评分,由两名不同人员分别进行活动度评估,根据目前临床通用标准[15],SLEDAI评分为0~4分者判断为无病情活动,>4分者判断为病情活动。

1.3 资料收集与方法从南昌大学第一附属医院的电子病历中采集患者完善胸部CT检查之前的临床数据,包括年龄、性别、SLE病程、合并症数量(包括肾功能不全、心血管疾病、糖尿病、甲状腺功能减退症、骨质疏松、哮喘、肝功能不全、脑梗死等)、糖皮质激素剂量和实验室数据[血常规、肝肾功能、CRP和红细胞沉降率(ESR)]。计算中性粒细胞/淋巴细胞(NLR)、血小板/淋巴细胞(PLR)、单核细胞/淋巴细胞(MLR)、CRP/淋巴细胞(CLR)、系统性免疫炎症指数(SII)、系统性免疫炎症指数/清蛋白(SII/ALB)。所有患者采集适量静脉血送检,采用全自动血液细胞分析仪(日本东亚公司,SYSMEX XN-10)检测血常规;采用全自动免疫分析仪(美国贝克曼库尔特公司,IMMAGE 800)检测血清CRP水平;采用全自动生化分析仪(日本日立公司,YQSH057 7600)检测肝肾功能。

1.4 统计学方法应用SPSS 26.0对数据进行统计分析。符合正态分布的计量资料用均数±标准差(x±s)表示,两组之间比较采用独立样本t检验,不符合正态分布的计量资料则采用中位数(四分位数)[M(P25,P75)]表示,两组之间采用Mann-Whitney U检验进行比较。计数资料以例数(百分比)表示,两组之间比较采用卡方检验或Fisher确切概率法。先后对数据进行单因素和多因素二元logistic回归分析。应用MedCalc软件绘制受试者工作特征(ROC)曲线,根据ROC曲线下面积(area under the curve, AUC)评估诊断价值。所有统计检验均为双侧检验,P≤0.05为差异有统计学意义。

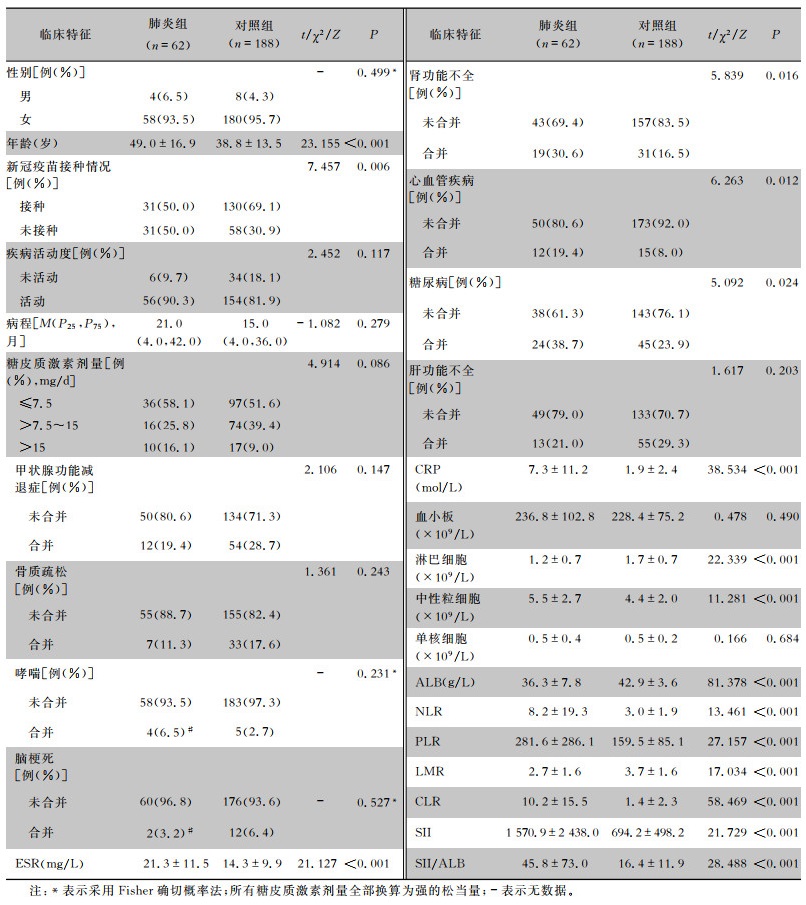

2 结果 2.1 一般资料共250例SLE合并COVID-19患者纳入本项研究,平均年龄为(41.4±15.1)岁。其中未发生肺炎患者188例(占75.2%),为对照组;发生肺炎患者62例(占24.8%),为肺炎组。本研究纳入的SLE患者以女性为主,占95.2%。对照组与肺炎组相比,两组患者在性别、疾病活动度、病程、糖皮质激素剂量、单核细胞水平、血小板水平等方面比较,差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05);肺炎组患者平均年龄高于对照组;有新冠疫苗接种史的患者在对照组中的占比高于肺炎组,差异均有统计学意义(均P<0.05)。肺炎组患者的ESR、CRP、中性粒细胞、NLR、PLR、CLR、SII和SII/ALB水平高于对照组;而ALB、LMR、淋巴细胞水平低于对照组,差异均有统计学意义(均P<0.05)。肺炎组患者合并肾功能不全、心血管疾病及糖尿病的患者比率高于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。见表 1。

| 表 1 两组患者的基线临床特征比较 Table 1 Comparison of baseline clinical characteristics between two groups of patients |

|

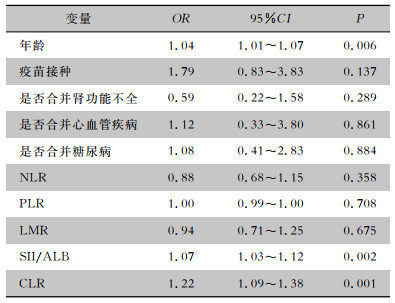

将年龄、是否接种疫苗、是否合并肾功能不全、是否合并心血管疾病、是否合并糖尿病、NLR、PLR、LMR、SII/ALB和CLR纳入二元logistic回归模型,多因素logistic回归分析提示年龄(OR=1.04,95%CI: 1.01~1.07)、SII/ALB(OR=1.07,95%CI: 1.03~1.12)及CLR(OR=1.22,95%CI: 1.09~1.38)为SLE患者合并COVID-19后发生肺炎的独立危险因素(均P<0.05)。见表 2。

| 表 2 SLE患者发生新型冠状病毒肺炎的多因素logistic分析 Table 2 Multivariate logistic analysis on the occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in SLE patients |

|

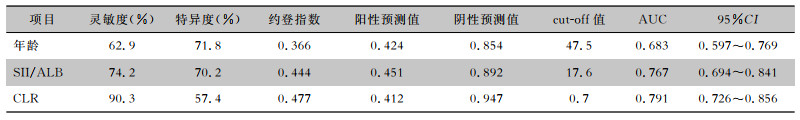

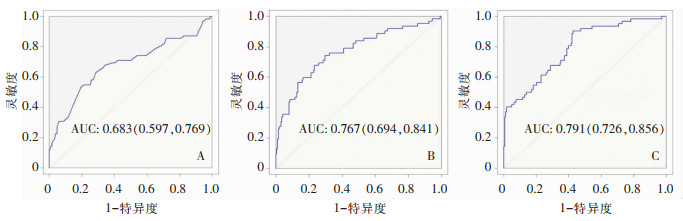

为进一步判断年龄、SII/ALB及CLR的诊断价值,绘制了ROC曲线。结果显示年龄AUC为0.683,其灵敏度为62.9%,特异度为71.8%;SII/ALB AUC为0.767,其灵敏度为74.2%,特异度为70.2%;CLR AUC为0.791,其灵敏度为90.3%,特异度为57.4%。与年龄及SII/ALB相比,CLR有更大的AUC,有更佳的诊断价值。见表 3、图 1。

| 表 3 年龄、SII/ALB和CLR诊断肺炎发生的ROC曲线分析 Table 3 ROC curve analysis of age, SII/ALB, and CLR to diagnose the occurrence of pneumonia |

|

|

| 注:A为年龄的ROC曲线图;B为SII/ALB的ROC曲线图;C为CLR的ROC曲线图。 图 1 不同指标诊断肺炎的ROC曲线图 Figure 1 ROC curve for diagnosing pneumonia by different indicators |

对包括SLE在内的风湿病患者而言,由于潜在的免疫失调风险及免疫抑制药物的使用,使得这部分特殊人群在面对COVID-19大流行时有着更大的风险。据全球风湿病联盟(GRA)的报告显示,与普通人群相比,SLE患者有着更高的住院率(46%)和病死率(9%)[16]。虽然接种COVID-19疫苗可以极大的降低感染率和死亡风险,但SLE患者接种疫苗效果较差,特别是接受糖皮质激素治疗的患者[17-18]。目前,新型冠状病毒肺炎是SLE患者住院和死亡的常见原因。因此,迫切需要在SLE患者中发现能够在早期简捷有效地识别新型冠状病毒肺炎的措施和方法。

过度且不受控制的细胞因子产生在COVID-19的发病机制中起着重要作用[19]。病毒通过血管紧张素转换酶受体进入肺泡细胞,触发细胞释放炎症因子,从而激活肺泡组织中的巨噬细胞。巨噬细胞释放的诱导因子和趋化因子导致单个核细胞在肺组织中聚集。炎症细胞的极端浸润诱导细胞因子风暴,导致急性肺损伤和急性呼吸窘迫综合征,严重时危及生命[20]。目前已有众多研究[21-23]报道,COVID-19患者中性粒细胞计数显著增加,淋巴细胞计数明显降低,本研究也获得了同样的结果。COVID-19患者淋巴细胞计数下降主要是由于CD4+T细胞和B细胞的减少[24]。而COVID-19患者中性粒细胞上升,则可能与淋巴细胞减少密切相关[25-26]。CRP是肝脏中由白细胞介素-6(IL-6) 诱导的非特异性急性期蛋白,是炎症、感染和组织损伤的敏感生物标志物。CRP的表达水平通常较低,但其在急性炎症反应中迅速显著升高[27]。CRP的升高单独或联合其他标志物可能揭示细菌或病毒感染[28]。与中性粒细胞及淋巴细胞等单个指标相比,一些新型的炎症标志物已被证实与COVID-19患者的肺炎等结局指标有高度相关性[29-31]。

本研究结果显示,与未发生新型冠状病毒肺炎的SLE患者相比,合并新型冠状病毒肺炎患者的年龄、中性粒细胞、ESR、CRP、NLR、PLR、CLR、SII和SII/ALB等指标升高,而淋巴细胞降低。同时,通过建立多因素回归分析模型发现年龄、SII/ALB及CLR是SLE患者合并COVID-19后发生肺炎的独立危险因素。为了进一步分析年龄、SII/ALB及CLR三者之间的诊断能力,绘制ROC曲线,结果表明,CLR的AUC值(0.791)高于年龄(0.683)和SII/ALB(0.767),具有更佳的诊断价值。

本文也存在一定的局限性。第一,由于本研究采取的是单中心研究设计,可能受SLE病情偏倚的影响;与多中心研究相比,其受试者群体的纳入不具有更充分的代表性。第二,本研究为回顾性研究,所涵盖的样本量相对较小,后续需要进行大规模、前瞻性的多中心研究以进一步论证本研究结果。

综上所述,本研究结果显示年龄、SII/ALB和CLR是SLE患者合并COVID-19后发生肺炎的危险因素。对于具备这些特征的人群,在临床中应给予更多的关注,以便后续选择更精准的治疗策略,从而为提高患者的治疗效果提供更有力的支持。

利益冲突:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

| [1] |

Ludwig S, Zarbock A. Coronaviruses and SARS-CoV-2:a brief overview[J]. Anesth Analg, 2020, 131(1): 93-96. DOI:10.1213/ANE.0000000000004845 |

| [2] |

Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, et al. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19): a review[J]. JAMA, 2020, 324(8): 782-793. DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.12839 |

| [3] |

Ameer MA, Chaudhry H, Mushtaq J, et al. An overview of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) pathogenesis, classification, and management[J]. Cureus, 2022, 14(10): e30330. |

| [4] |

Tian JR, Zhang DY, Yao X, et al. Global epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comprehensive systematic analysis and modelling study[J]. Ann Rheum Dis, 2023, 82(3): 351-356. DOI:10.1136/ard-2022-223035 |

| [5] |

Saxena A, Engel AJ, Banbury B, et al. Breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infections, morbidity, and seroreactivity following initial COVID-19 vaccination series and additional dose in patients with SLE in New York City[J]. Lancet Rheumatol, 2022, 4(9): e582-e585. DOI:10.1016/S2665-9913(22)00190-4 |

| [6] |

Zhao W, Zhong Z, Xie XZ, et al. Relation between chest CT findings and clinical conditions of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia: a multicenter study[J]. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2020, 214(5): 1072-1077. DOI:10.2214/AJR.20.22976 |

| [7] |

Nakajima K, Kato H, Yamashiro T, et al. COVID-19 pneumonia: infection control protocol inside computed tomography suites[J]. Jpn J Radiol, 2020, 38(5): 391-393. DOI:10.1007/s11604-020-00948-y |

| [8] |

Liu J, Li SM, Liu J, et al. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients[J]. EBioMedicine, 2020, 55: 102763. DOI:10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102763 |

| [9] |

Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease[J]. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2014, 6(10): a016295. DOI:10.1101/cshperspect.a016295 |

| [10] |

Peng JN, Qi D, Yuan GD, et al. Diagnostic value of periphe-ral hematologic markers for coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19): a multicenter, cross-sectional study[J]. J Clin Lab Anal, 2020, 34(10): e23475. DOI:10.1002/jcla.23475 |

| [11] |

Lagunas-Rangel FA. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and lymphocyte-to-C-reactive protein ratio in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19): a Meta-analysis[J]. J Med Virol, 2020, 92(10): 1733-1734. DOI:10.1002/jmv.25819 |

| [12] |

杨芸, 陈结慧, 祝胜郎. NLR联合CRP对肾移植受者远期感染的预测价值[J]. 中国免疫学杂志, 2023, 39(2): 380-384. Yang Y, Chen JH, Zhu SL. Diagnostic value of NLR combined CRP in predicting long-term infection of KTRs[J]. Chinese Journal of Immunology, 2023, 39(2): 380-384. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-484X.2023.02.029 |

| [13] |

赵文慧, 徐冬祥, 安仲武, 等. 中性粒细胞/淋巴细胞比值、肿瘤坏死因子α和C反应蛋白对慢性骨髓炎的诊断价值[J]. 中国感染与化疗杂志, 2022, 22(6): 708-712. Zhao WH, Xu DX, An ZW, et al. Utility of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, TNF-α, and C-reactive protein in diagnosing chronic osteomyelitis[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy, 2022, 22(6): 708-712. DOI:10.16718/j.1009-7708.2022.06.009 |

| [14] |

Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumato-logy classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. Ann Rheum Dis, 2019, 78(9): 1151-1159. DOI:10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214819 |

| [15] |

Jesus D, Matos A, Henriques C, et al. Derivation and validation of the SLE disease activity score (SLE-DAS): a new SLE continuous measure with high sensitivity for changes in disease activity[J]. Ann Rheum Dis, 2019, 78(3): 365-371. DOI:10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214502 |

| [16] |

Gianfrancesco M, Hyrich KL, Al-Adely S, et al. Characteristics associated with hospitalisation for COVID-19 in people with rheumatic disease: data from the COVID-19 global rheumatology alliance physician-reported registry[J]. Ann Rheum Dis, 2020, 79(7): 859-866. DOI:10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217871 |

| [17] |

Montero F, Martínez-Barrio J, Serrano-Benavente B, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19) in autoimmune and inflammatory conditions: clinical characteristics of poor outcomes[J]. Rheumatol Int, 2020, 40(10): 1593-1598. DOI:10.1007/s00296-020-04676-4 |

| [18] |

Lee ARYB, Wong SY, Chai LYA, et al. Efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in immunocompromised patients: systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. BMJ, 2022, 376: e068632. |

| [19] |

Sun XJ, Wang TY, Cai DY, et al. Cytokine storm intervention in the early stages of COVID-19 pneumonia[J]. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 2020, 53: 38-42. DOI:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.04.002 |

| [20] |

Wan YS, Shang J, Graham R, et al. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus[J]. J Virol, 2020, 94(7): e00127-20. |

| [21] |

Mathian A, Mahevas M, Rohmer J, et al. Clinical course of coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19) in a series of 17 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus under long-term treatment with hydroxychloroquine[J]. Ann Rheum Dis, 2020, 79(6): 837-839. DOI:10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217566 |

| [22] |

Gartshteyn Y, Askanase AD, Schmidt NM, et al. COVID-19 and systemic lupus erythematosus: a case series[J]. Lancet Rheumatol, 2020, 2(8): e452-e454. DOI:10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30161-2 |

| [23] |

Holubar J, Le Quintrec M, Letaief H, et al. Monitoring of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus during the COVID-19 outbreak[J]. Ann Rheum Dis, 2021, 80(4): e56. DOI:10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217919 |

| [24] |

Zucchi D, Tani C, Elefante E, et al. Impact of first wave of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: weighting the risk of infection and flare[J]. PLoS One, 2021, 16(1): e0245274. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0245274 |

| [25] |

Cordtz R, Kristensen S, Dalgaard LPH, et al. Incidence of COVID-19 hospitalisation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a nationwide cohort study from Denmark[J]. J Clin Med, 2021, 10(17): 3842. DOI:10.3390/jcm10173842 |

| [26] |

Bachiller-Corral J, Boteanu A, Garcia-Villanueva MJ, et al. Risk of severe COVID-19 infection in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases[J]. J Rheumatol, 2021, 48(7): 1098-1102. DOI:10.3899/jrheum.200755 |

| [27] |

Herold T, Jurinovic V, Arnreich C, et al. Elevated levels of IL-6 and CRP predict the need for mechanical ventilation in COVID-19[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2020, 146(1): 128-136.e4. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.008 |

| [28] |

Liu F, Li L, Xu MD, et al. Prognostic value of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin in patients with COVID-19[J]. J Clin Virol, 2020, 127: 104370. DOI:10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104370 |

| [29] |

Yang AP, Liu JP, Tao WQ, et al. The diagnostic and predictive role of NLR, d-NLR and PLR in COVID-19 patients[J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2020, 84: 106504. DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106504 |

| [30] |

Sun SY, Cai XJ, Wang HG, et al. Abnormalities of peripheral blood system in patients with COVID-19 in Wenzhou, China[J]. Clin Chim Acta, 2020, 507: 174-180. DOI:10.1016/j.cca.2020.04.024 |

| [31] |

Mehta P, Gasparyan AY, Zimba O, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic: infection, vaccination, and impact on disease management[J]. Clin Rheumatol, 2022, 41(9): 2893-2910. DOI:10.1007/s10067-022-06227-7 |