Research progress on antiviral effects of immunosuppressants

-

摘要: 免疫抑制剂主要用于降低实体器官移植后发生的排斥反应,从而提高器官移植的成功率。然而,免疫抑制剂长期使用也会严重影响患者机体的免疫功能,进而增加患者感染病毒类疾病以及术后并发症导致移植失败的风险。因此,患者需要在服用免疫抑制剂的同时也服用抗病毒药物。若发现一些具有抗病毒效果的免疫抑制剂,将大大减轻患者服用药物的负担。目前,具有抗病毒效果的免疫抑制剂已被研究人员关注。这些免疫抑制剂抗病毒机制的逐步揭示,有助于优化器官移植受者术后康复的治疗方案。基于机体对移植器官产生排异反应的机制,本文系统阐述了与器官移植患者感染密切相关的病毒种类以及一些免疫抑制剂在抗病毒方面的分子机制,进一步为临床上预防和治疗器官移植引发病毒性感染提供新的思路。Abstract: Immmunosuppressants are mainly used to reduce rejection after solid organ transplantation, so as to improve the success rate of organ transplantation. However, long-term use of immunosuppressants can also seriously impair the immune function of patients, thereby increasing the risk of viral infection and postoperative complications, leading to transplant failure. Therefore, patients need to use both immunosuppressants and antiviral agents. If some immunosuppressants with antiviral effects are found, the patient's burden of taking medicines will be greatly reduced. Currently, the immunosuppressants with antiviral effect have been focused by researchers. The gradual revealing of the antiviral mechanism of these immunosuppressants will help to optimize the treatment plan of postope-rative rehabilitation of organ transplant recipients. Based on the mechanism of rejection of transplanted organ, this paper systematically describes the types of viruses which closely related to infection of organ transplant patients and the molecular mechanism of some immunosuppressants in antiviral aspects, which further provides a new idea for clinical prevention and treatment of viral infection due to organ transplantation.

-

Keywords:

- solid organ transplantation /

- rejection /

- immunosuppressant /

- antivirus /

- mechanism

-

实体器官移植(solid organ transplantation, SOT)仍是罹患终末期器官疾病患者为数不多的选择之一。为了提高实体器官移植受者的生存率,临床治疗上非常重视免疫抑制剂(immunosuppre-ssant)的使用时长以及药物种类的选择[1]。然而,长期使用免疫抑制剂会使实体器官移植受者免疫系统处于抑制状态,增加了移植受者多种病毒感染的风险,诸如疱疹病毒、巨细胞病毒(cytomegalovirus, CMV)、EB病毒、流感病毒、新型冠状病毒(SARS-CoV-2)、乙型肝炎病毒(hepatitis B virus, HBV)和丙型肝炎病毒(hepatitis C virus, HCV)等。器官移植的受者在使用免疫抑制剂的过程中一旦遭受病毒侵染,将大大增加受者实体器官移植失败的风险,甚至会引发死亡。当前,实体器官移植受者所能选择的临床治疗手段主要围绕着预防性用药、定期复查以及抗病毒治疗等策略开展。对移植受者来说,一个无法回避的事实就是长期服用免疫抑制剂降低排斥反应的同时还需要接受抗病毒治疗。这不仅增加了移植受者机体代谢药物的负担,也容易出现耐受抗病毒药物的变异毒株。针对上述移植受者长期服用免疫抑制剂带来的现实挑战,本文将系统阐述免疫抑制剂造成机体免疫力低下对病毒侵染机体提供良机的机制,以及当前一些具有抗病毒活性的免疫抑制剂在抗病毒方面的机制。本文旨在为实体器官移植受者临床用药方面提供一些新线索,为临床医生为受者选择抗病毒治疗方案提供新思路。

1. T细胞介导排斥的机制

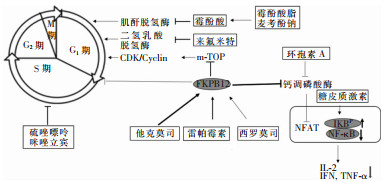

器官移植能有效延长器官衰竭终末期患者的生存时间,术后排斥反应是影响器官移植成功与否的关键因素。从免疫系统角度来看,由T淋巴细胞介导的排斥反应比抗体介导的排斥反应更为常见。在器官移植之后,外源抗原会不断刺激受者机体T淋巴细胞并使之活化。最终活化T淋巴细胞产生白细胞介素2(interleukin-2, IL-2)来开启排斥反应。这种情况下,使用免疫抑制剂来有效抑制T淋巴细胞的免疫活性对于降低排斥反应显得尤为重要。例如硫唑嘌呤可以降低DNA的合成并抑制细胞增殖;甲基泼尼松龙可以抑制某些促炎基因如IL-2、干扰素γ(interferon-γ, IFN-γ)、肿瘤坏死因子α(tumor necrosis factor-α, TFN-α)等的转录,减弱T淋巴细胞表达相关细胞因子;雷帕霉素可以抑制IL-2受体远端胞内信号的传导,因此可以抑制T淋巴细胞对细胞因子的反应。虽然上述免疫抑制剂可有效降低机体免疫反应对异体器官的排斥效应,但随之而来的便是感染病毒的概率显著增加。

2. 具有抗病毒功效的免疫抑制剂

对于器官移植患者来说,在长期服用免疫抑制类药物降低排斥反应的同时,还需要服用不同种类的抗病毒药物来预防/治疗不同病毒的感染,这必然为脏器代谢药物带来不小的负担。目前,临床使用的免疫抑制剂主要包括皮质固醇类的药物、钙调神经磷酸酶抑制剂、抗代谢药物、m-TOR抑制剂以及多克隆生物制剂等。这些免疫抑制剂通过抑制T细胞DNA复制和蛋白质表达来实现免疫抑制,见图 1。而病毒在复制过程中需要利用宿主系统来合成病毒颗粒组装所需的遗传物质和蛋白质。这就意味着,某些免疫抑制剂发挥免疫抑制作用的同时也存在潜在的抗病毒效果。

2.1 来氟米特(leflunomide)

来氟米特是一种被批准用于治疗类风湿性关节炎的药物,在肝脏、肠道中可以转化为代谢活性形式A77-1726,其活性形式通过以下机制发挥其免疫调节作用:(1)通过抑制二氢乳清酸脱氢酶(dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, DHODH)来阻止T细胞增殖,DHODH是嘧啶核苷酸生物合成中的关键限速酶。来氟米特通过抑制DHODH活性来干扰嘧啶合成。这将对细胞周期G1期的顺利执行造成可逆性干扰,从而影响细胞分裂[2-3];(2)抑制蛋白酪氨酸激酶以及丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(mitogen-activated protein kinase, MAPK)活性,阻止蛋白磷酸化,最终实现抗病毒效应[4];(3)通过阻止核因子κB(nuclear factor κB, NF-κB)的活化,阻止lκB的降解及其核易位,最终干扰TNF-α和其他炎症细胞因子的合成及活性[5];(4)调节T辅助淋巴细胞亚群分化[6]。临床研究[7-11]表明,来氟米特单独用药或者联合糖皮质激素(glucocorticoid, GC)/免疫调节剂可改善类风湿性关节炎(rheumatoid arthritis, RA)、狼疮性肾炎(lupus nephritis, LN)、肉芽肿性多血管炎(granulomatosis with polyangiitis, GPA)、巨细胞动脉炎(giant cell arteritis, GCA)和大动脉炎(takayasu arteritis, TA)的临床症状。

研究来氟米特血浆中的药代动力学过程中发现,其半衰期约为3.5 h,但是其活性形式(A77-1726)的半衰期可长达360 h。临床医生根据血药稳态浓度(steady-state concentration, Css)来制定临床用药的剂量为100 mg/d,连续服用3 d之后维持量为10~20 mg/d[12]。根据来氟米特的药代动力学特征,其活性形式在机体内发挥生物活性的长效性展现出其抗病毒的潜质。来氟米特通过抑制蛋白酪氨酸激酶的活性,有效干扰病毒基因组复制以及蛋白产物磷酸化等过程,最终发挥抗病毒效应。来氟米特对多种病毒具有抗病毒活性,例如CMV、BK多瘤病毒、单纯疱疹病毒(herpes simplex virus, HSV)、呼吸道合胞病毒(respiratory syncytial virus, RSV)和SARS-CoV-2等[13-15]。例如,无论体内试验还是体外试验,来氟米特在抵抗CMV侵染宿主细胞方面均展现出很强的临床治疗潜力[16-18]。此外,来氟米特可以通过诱导细胞产生非特异性嘧啶耗竭,有效抑制BK多瘤病毒在肾小管上皮细胞中的增殖[19]。其活性代谢物(A77-1726)在降低RSV在细胞水平以及小鼠肺部感染程度上均表现出剂量依赖性的药物学特征[20]。在研究A77-1726抗鸠宁病毒(Junín virus, JUNV)感染过程中,研究者发现A77-1726能够以剂量依赖性的形式诱导嘧啶枯竭,最终阻止JUNV相关RNA的合成[21]。多发性硬化症患者在接受A77-1726临床治疗的过程中,明显表现出对SARS-CoV-2感染具有抗病毒活性,使患者表现出较轻的临床症状[22]。

凭借其免疫抑制功能以及抗病毒效应,来氟米特在器官移植受者治疗免疫排斥反应以及预防病毒侵染方面备受青睐。但是来氟米特临床使用剂量的不同可能会影响其免疫抑制和抗病毒的功效,例如,研究人员发现高剂量来氟米特用于肾脏移植患者的治疗过程中,免疫抑制效应失衡并且明显削弱了其抗病毒能力[23]。在治疗耐更昔洛韦CMV感染的肾脏移植患者时,低剂量来氟米特不仅能够维持免疫抑制,还能够有效清除患者体内CMV耐药毒株[24]。可见器官移植受者在使用来氟米特临床预防免疫排斥反应以及病毒侵染的过程中的用药剂量对治疗效果极为重要。

2.2 霉酚酸(mycophenolic acid, MPA)

MPA是酯前药吗替麦考酚酯(mycophenolate mofetil, MMF) 的活性代谢产物,具有免疫抑制活性,临床上预防肾脏、心脏或肝脏移植后的移植物排斥反应[25]。临床常用的MPA通常有霉酚酸酯普通片、分散片、胶囊和霉酚酸钠肠溶片。MPA在机体的半衰期约为17.9 h,大多数以与血浆蛋白结合的形式存在并且表现出明显的肝肠循环特征[26]。MPA通过选择性抑制肌苷脱氢酶(inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase, IMPDH)在嘌呤合成的途径中发挥其免疫抑制活性,最终导致T淋巴细胞和B淋巴细胞增殖能力降低[27]。

除了免疫抑制作用,包括本团队的相关研究[28-30]发现MPA具有广谱抗病毒作用。MPA兼备免疫抑制及抗病毒活性使其在器官移植受者临床治疗免疫排斥及病毒侵染中具有巨大的潜力。与其它抗病毒药物不同,MPA通过耗尽宿主细胞的鸟苷酸来抑制病毒复制,可降低耐药病毒株出现概率。例如,MPA无论在细胞水平还是小鼠感染模型上均发挥出对日本脑炎病毒显著的抗病毒效果[31]。针对SARS-CoV-2侵染,虽然MPA只能使其RNA合成水平降低2个数量级,但MPA仅仅需要0.85 μmol/L的半数最大效应浓度(concentration for 50% of maximal effect, EC50)的剂量就可达到上述抗病毒效果[29],这为后续深入评估临床服用MPA的免疫缺陷患者抵抗SARS-CoV-2感染产生的临床症状轻重提供了参考依据。在抵抗人类猴痘病毒的体外研究中也同样发现MPA对病毒基因组转录活性具有很强的抑制效应[32]。轮状病毒(rotavirus, RV)的高突变性是其难以有效治疗的因素之一。然而,MPA在10 μg/mL的治疗剂量下对RV基因组合成的抑制率高达99%[33]。表明MPA对RV基因组突变具有很高的耐药屏障,与MPA的抗病毒机制密不可分。EB病毒可以通过EBNA2途径和Myc途径诱导IMPDH2表达,导致核仁、细胞核和细胞的肥大以及有效的细胞增殖。研究[34]发现,使用MMF可抑制淋巴细胞增生性疾病。因此,IMPDH2抑制剂,即MPA或MMF,可用于EB病毒阳性移植后淋巴细胞增生性疾病的临床治疗。与利巴韦林对登革热病毒的抗病毒效果相比,MPA以EC50为0.4 μmol/L的剂量就可以明显抑制登革热病毒(dengue virus, DENV) 在猴肾细胞中的增殖活性,远远超过利巴韦林对此病毒的抗病毒效果[35]。无论产业化生产还是临床使用,MPA都是十分成熟的一种免疫抑制剂药物[36],深入研究其对不同病毒的抗病毒机制,将对器官移植受者后期免疫治疗过程中“一石二鸟”有效防控病毒感染提供有利支持。

2.3 咪唑立宾(mizoribine)

咪唑立宾是一种咪唑类核苷药物,凭借对T、B淋巴细胞的抗增殖、分化的活性,咪唑立宾已经用于肾脏移植受者的后期治疗中,在日本被批准用于预防器官异体移植排斥反应,以及治疗RA、原发性肾病、LN、皮肌炎和自身免疫性皮肤病。同样,作为一种IMPDH抑制剂,咪唑立宾能够抑制鸟苷单磷酸分子的合成,其活性代谢产物咪唑立宾5’-MP被认为可以模拟IMPDH催化的过渡状态,其在抗病毒活性方面也表现不俗,包括对RSV、甲/乙型流感病毒、副流感病毒2型和3型、腮腺炎病毒、麻疹病毒、CMV、HSV、SARS-CoV-2、HCV等的抗病毒活性[37-38]。与利巴韦林的抗病毒活性相比,咪唑立宾对多种病毒的抗病毒活性仅需要EC50值为亚微摩尔级别就可实现。由于牛病毒性腹泻病毒(bovine viral diarrhea virus, BVDV) 在病毒复制以及致病机制方面与HCV十分相似,因此很多研究是以研究BVDV感染机制来揭示HCV的相关致病机制。在抑制BVDV在牛肾细胞中的增殖活性方面,当咪唑立宾单独处理感染细胞时,其抗病毒效应需要的EC50值为5.3 μmol/L;当咪唑立宾与IFN-α以10 ∶1的比例联合使用时,咪唑立宾表现出抗BVDV增殖的EC50值仅为0.66 μmol/L[39]。这一研究为后续评估咪唑立宾对HCV抗病毒效果的研究提供了有价值的参考依据[38]。临床治疗上,肾病综合征合并乙型病毒性肝炎的患者连续服用咪唑立宾(150~200 mg/24 h)、甲基强的松龙[0.6~ 0.8 mg/(kg·24 h)]和恩替卡韦(0.5 mg/24 h)24周后,患者临床症状显著缓解并且不良反应不明显[40]。该药物与阿昔洛韦联合使用,可以增强阿昔洛韦对疱疹病毒感染的治疗效果[41]。虽然咪唑立宾在免疫排斥以及病毒侵染中均表现不凡[42],但是高剂量用药还是会引起肾脏移植受者发生急性肾衰和高尿酸血症[43]。为改善肾脏器官移植受者的生存状态,咪唑立宾与他克莫司联合用药可避免上述病症的发生[44]。因此,咪唑立宾可以考虑用作临床中实体器官移植受者治疗及预防病毒感染的一种备选药物,也可以与其他药物联合使用,以增强药物的抗病毒作用。

2.4 环孢素(cyclosporin)

环孢素是一种钙调磷酸酶抑制剂。环孢素特异性选择T淋巴细胞,在T淋巴细胞中与亲环蛋白结合形成复合物,进而阻遏钙调磷酸酶的活性,使T淋巴细胞无法分泌IL-2。在治疗免疫排斥反应的过程中,如果同源异体移植导致黏膜炎症会妨碍受者对环孢素的吸收,影响免疫抑制效果[45]。此外,通过对器官移植受者若干基因(CYP3A4、ABCB1、ABCC2、ABCG2、NFKB1、POR和PXR)遗传多态性的分析,研究人员发现上述基因遗传多态性对于环孢素剂量有明显耐受差异[46],这也给临床医生使用环孢素进行免疫抑制治疗时的剂量调整提供了有价值的参考信息。

当接受同种异体骨髓移植的HCV阳性患者服用环孢素A(cyclosporin A, CsA)的剂量逐步降低时,其血清中的HCV核心蛋白的水平将升高,并出现肝炎症状,HCV再激活和增殖可能是HCV抗体阳性患者骨髓移植后出现肝炎症状的原因之一[47]。在抗HCV感染中,环孢素通过干扰病毒后期粒子包装活性来快速抑制胞外感染性HCV的病毒载量[48]。宿主蛋白亲环蛋白A(cyclophilin A, CyPA)在黄病毒复制中发挥至关重要的作用,可抑制黄病毒在细胞中的增殖活性。其机制是亲环素直接阻断细胞CyPA与黄病毒非结构蛋白5(nonstructural protein, NS5)的相互作用。因此,环孢素是抗黄病毒临床用药的候选者[49]。通过体内/外研究,发现CsA对中东呼吸综合征冠状病毒(MERS-CoV)、SARS-CoV-2以及新出现的病毒变体均有抗病毒作用,而CsA的这种对冠状病毒科成员的广泛抗病毒效应也突显了CsA应用于临床治疗的潜在价值[50-51]。同样是通过抑制环孢素特异性胞内受体CyPA,环孢素诱导机体产生固有免疫以及一系列抗病毒基因对具有囊膜的不同RNA病毒也有抗病毒效果[52-54]。在SARS-CoV-2感染仍旧频发的大环境给器官移植受者带来一丝曙光,同时也为免疫治疗过程中预防SARS-CoV-2感染提供有价值的参考资料。在抵抗流感病毒侵染的过程中,虽然CsA不能影响病毒对A549细胞的吸附、内化、基因组复制以及蛋白合成,但是CsA可以干扰病毒粒子的组装和出芽。这也为进一步将CsA开发成免疫抑制患者临床抗流感病毒感染的治疗性药物提供有价值的参考依据。

2.5 雷帕霉素(rapamycin)

雷帕霉素是一种大环内酯类药物,因其不良反应小,免疫抑制效果好,一直是器官移植受者常用的一种免疫抑制剂。在诸多免疫抑制途径中,雷帕霉素能够促进Treg细胞的增殖来增强对机体免疫活力的抑制。2021年Yang等[55]将一种程序性死亡受体的配基(PD-L1)与雷帕霉素联合使用,能够降低T淋巴细胞的免疫活性并且提高Treg细胞增殖活性,双管齐下实现对机体免疫活性的抑制。借助肾脏移植模型来评估雷帕霉素的免疫抑制功效,研究人员发现雷帕霉素能够阻断促炎反应相关因子MCP-1、IL-1β及TNF-α的表达,最终阻止幼稚型细胞发生衰老反应[56]。除免疫抑制方面表现突出,雷帕霉素在阻断特异性受体活性中还会表现出广谱的抗病毒活性[57-58],见表 1。随着研究深入,雷帕霉素在免疫抑制以及抗病毒方面的新发现将对其广泛应用于器官移植受者治疗增加依据。

表 1 雷帕霉素的抗病毒效应病毒 雷帕霉素的抗病毒途径 CMV 促进CD8+T细胞分化增殖 EBV 降低BZLF1转录活性以及改变病毒基因转录活性 HIV 减少CCR5受体的表达水平以及增加抗病毒成分T20的水平 HCV 阻遏mTORC1受体的活性来降低病毒RNA的复制 流感病毒 阻遏自噬发生,从而在某种程度上减缓病毒的复制 作为HBV感染的潜在治疗药物,雷帕霉素强烈抑制HBV表面大抗原(large surface antigen, LHBs)与HBV进入受体牛磺胆酸钠共转运多肽(sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide, NTCP)之间的结合与互相作用,从而降低HBV侵染肝细胞的能力。此外,雷帕霉素还可以预防同样利用NTCP进入细胞的丁型肝炎病毒的感染[59]。BZLF1转录本在EB病毒生命周期早期的相关基因复制及表达发挥重要作用,雷帕霉素抑制mTOR通路可降低BZLF1转录本的总水平,严重干扰EB病毒生命周期的完成,最终降低EB病毒在细胞中的增殖活力[60]。此外,EB病毒突变产生的不同类型突变体对应的转录本均能被雷帕霉素通过抑制mTOR通路降低其转录水平,所导致转录本差异表达可干扰EB病毒正常的复制周期[61]。

关于人类免疫缺陷病毒(HIV)感染,雷帕霉素在体外处理CD4+T淋巴细胞可降低其CCR5(病毒进入细胞所必需的共受体)密度并抑制CCR5依赖性病毒粒子HIV-1复制。雷帕霉素可以改善T-20(一种用于治疗HIV的融合抑制剂肽)的抗病毒活性[62]。研究[63-65]表明,雷帕霉素可用于临床治疗,以增强T-20对HIV的抗病毒作用,进而增加其他靶向CCR5的药物的抗病毒作用。此外,雷帕霉素作为临床用药的另一个突出优点是:利用雷帕霉素进行临床治疗,不会干扰细胞毒性T淋巴细胞(cytotoxic T lymphocyte, CTL)对HIV的特异性识别或对HIV感染细胞的杀伤活性[66]。

当今,SARS-CoV-2感染仍旧严重威胁人类健康。重度SARS-CoV-2感染患者会由于机体产生的炎症风暴而威胁其生命安全。而炎症风暴的产生与机体大量释放包括IL-2、IL-7、IL-10、单核细胞趋化蛋白1(monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, MCP-1)、巨噬细胞炎症蛋白(macrophage inflammatory protein 1α, MIP1α)和TNF-α等细胞因子相关[67]。雷帕霉素是一种免疫抑制剂,由于其能够减少IL-6、IL-2和IL-10等细胞因子的分泌,因此可以潜在地控制SARS-CoV-2感染患者体内产生炎症风暴。

2.6 6-硫鸟嘌呤(6-thioguanine, 6-TG)

6-TG是抗代谢药物6-硫代嘌呤的前体药物,早已被广泛用于治疗自身免疫性疾病,如炎症性肠病和器官移植后期治疗等。有关药物毒性的临床研究[68]发现,6-TG的细胞毒性阈值为0.05 μmol/L。源自6-TG前体药物的6-TGNP与Rac1结合形成6-TGNP-Rac1复合物,它的形成通过阻断T淋巴细胞介导的Rac1活化来诱导免疫抑制。除了其免疫抑制活性,6-TG在抗病毒领域也焕发活力。例如,6-TG能够通过抑制宿主蛋白Rac1形成GTP-Rac1活性形式,干扰轮状病毒和HSV的增殖活性[69-70]。6-TG在治疗HSV感染上比阿昔洛韦和更昔洛韦更有效,体外试验表明仅需0.104 μmol/L的药物浓度,即可抑制50%的病毒感染。再者,6-TG对阿昔洛韦耐药的HSV-1毒株同样有效[70]。2022年Pringle等[71]发现6-TG可在病毒感染早期就抑制病毒基因组复制、亚基因组转录以及结构蛋白合成,在该过程中,6-TG首先要通过次黄嘌呤-磷酸核糖转移酶1将其转变为核苷形式来抑制冠状病毒的复制,然而抗病毒活性并没有涉及到抑制GTP酶的活性。利用细胞模型和类器官感染模型对6-TG抗SARS-CoV-2能力的研究中,6-TG对SARS-CoV-2野生型以及突变型毒株均表现出明显的抑制病毒增殖的抗病毒活性[30]。在研究6-TG抗IAV感染机制的过程中,研究人员发现6-TG能够诱发感染细胞形成应激颗粒(stress granule, SG),最终干扰IAV在细胞中的增殖;然而,6-TG并不会诱导未被IAV感染的细胞产生SGS来干扰细胞的生物活性。此外,6-TG还可以选择性破坏IAV的血凝素蛋白和神经氨酸酶的表达及后期活化,但是6-TG不能干扰相应病毒基因的复制活性[72]。6-TG在抗病毒活性方面所展现出来的活力让病毒学家眼前一亮,有望在器官移植受者免疫抑制治疗过程中预防特定病毒侵染。

3. 总结与展望

实体器官移植受者作为一类特殊的群体,必须同时应对机体对外来移植物的排斥反应以及病毒感染的威胁。同时使用免疫抑制剂和抗病毒药物虽然是目前常见的临床疗法,但不同药物的叠加可能会出现配伍禁忌并增加机体代谢负担。有效开发利用现有临床类免疫抑制剂在抗病毒方面的新功能可为后期治疗器官移植受者提供新路径。随着免疫抑制剂抗病毒效应的不断发现,其抗病毒机制与其介导的免疫抑制机制之间的关联是今后此领域研究的焦点之一。此外,积极收取临床使用免疫抑制剂患者预防或者被感染的数据,这将给研究免疫抑制剂的抗病毒效果以及安全性方面带来积极作用,让研究人员有的放矢,而不是无目的药物筛选,有效节约研究成本。同时,这也为缩短具有抗病毒活性的免疫抑制剂类药物应用于临床治疗的评价周期提供有力支持。

-

表 1 雷帕霉素的抗病毒效应

病毒 雷帕霉素的抗病毒途径 CMV 促进CD8+T细胞分化增殖 EBV 降低BZLF1转录活性以及改变病毒基因转录活性 HIV 减少CCR5受体的表达水平以及增加抗病毒成分T20的水平 HCV 阻遏mTORC1受体的活性来降低病毒RNA的复制 流感病毒 阻遏自噬发生,从而在某种程度上减缓病毒的复制 -

[1] 徐亚男, 郭易难, 吴昌鸿, 等. 器官移植免疫学研究前沿及进展[J]. 实用器官移植电子杂志, 2022, 10(4): 289-294. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-5332.2022.04.001 Xu YN, Guo YN, Wu CH, et al. Frontiers and progress of organ transplantation immunology research[J]. Practical Journal of Organ Transplantation(Electronic version), 2022, 10(4): 289-294. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-5332.2022.04.001 [2] Perricone C, Triggianese P, Bartoloni E, et al. The anti-viral facet of anti-rheumatic drugs: lessons from COVID -19[J]. J Autoimmun, 2020, 111: 102468. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102468 [3] Munier-Lehmann H, Vidalain PO, Tangy F, et al. On dihydroorotate dehydrogenases and their inhibitors and uses[J]. J Med Chem, 2013, 56(8): 3148-3167. doi: 10.1021/jm301848w [4] Vergne-Salle P, Léger DY, Bertin P, et al. Effects of the active metabolite of leflunomide, A77 1726, on cytokine release and the MAPK signalling pathway in human rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes[J]. Cytokine, 2005, 31(5): 335-348. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.06.002 [5] Manna SK, Aggarwal BB. Immunosuppressive leflunomide metabolite (A77 1726) blocks TNF-dependent nuclear factor-ka-ppa B activation and gene expression[J]. J Immunol, 1999, 162(4): 2095-2102. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.162.4.2095 [6] Moon SJ, Kim EK, Jhun JY, et al. The active metabolite of leflunomide, A77 1726, attenuates inflammatory arthritis in mice with spontaneous arthritis via induction of heme oxyge-nase-1[J]. J Transl Med, 2017, 15(1): 31. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1131-x [7] Strand V, Cohen S, Schiff M, et al. Treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis with leflunomide compared with placebo and methotrexate. Leflunomide Rheumatoid Arthritis Investigators Group[J]. Arch Intern Med, 1999, 159(21): 2542-2550. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.21.2542 [8] An Y, Zhou YS, Bi LQ, et al. Combined immunosuppressive treatment (CIST) in lupus nephritis: a multicenter, rando-mized controlled study[J]. Clin Rheumatol, 2019, 38(4): 1047-1054. doi: 10.1007/s10067-018-4368-8 [9] Henes JC, Fritz J, Koch S, et al. Rituximab for treatment-resistant extensive Wegener's granulomatosis-additive effects of a maintenance treatment with leflunomide[J]. Clin Rheumatol, 2007, 26(10): 1711-1715. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0643-9 [10] Adizie T, Christidis D, Dharmapaliah C, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of leflunomide in difficult-to-treat polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis: a case series[J]. Int J Clin Pract, 2012, 66(9): 906-909. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02981.x [11] Cui XM, Dai XM, Ma LL, et al. Efficacy and safety of leflunomide treatment in Takayasu arteritis: case series from the East China cohort[J]. Semin Arthritis Rheum, 2020, 50(1): 59-65. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.06.009 [12] Alamri RD, Elmeligy MA, Albalawi GA, et al. Leflunomide an immunomodulator with antineoplastic and antiviral potentials but drug-induced liver injury: a comprehensive review[J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2021, 93: 107398. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107398 [13] Ehlert K, Groll AH, Kuehn J, et al. Treatment of refractory CMV-infection following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with the combination of foscarnet and leflunomide[J]. Klin Padiatr, 2006, 218(3): 180-184. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-933412 [14] Bernhoff E, Tylden GD, Kjerpeseth LJ, et al. Leflunomide inhibition of BK virus replication in renal tubular epithelial cells[J]. J Virol, 2010, 84(4): 2150-2156. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01737-09 [15] Kramarič J, Ješe R, Tomšič M, et al. COVID-19 among patients with giant cell arteritis: a single-centre observational study from Slovenia[J]. Clin Rheumatol, 2022, 41(8): 2449-2456. doi: 10.1007/s10067-022-06157-4 [16] Chacko B, John GT. Leflunomide for Cytomegalovirus: bench to bedside[J]. Transpl Infect Dis, 2012, 14(2): 111-120. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00682.x [17] Haynes LD, Waldman WJ, Bushkin Y, et al. CMV-infected allogeneic endothelial cells initiate responder and bystander donor HLA class I release via the metalloproteinase cleavage pathway[J]. Hum Immunol, 2005, 66(3): 211-221. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.12.005 [18] Zeng HS, Waldman WJ, Yin DP, et al. Mechanistic study of malononitrileamide FK778 in cardiac transplantation and CMV infection in rats[J]. Transplantation, 2005, 79(1): 17-22. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000137334.46155.94 [19] Faguer S, Hirsch HH, Kamar N, et al. Leflunomide treatment for polyomavirus BK-associated nephropathy after kidney transplantation[J]. Transpl Int, 2007, 20(11): 962-969. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00523.x [20] Dunn MCC, Knight DA, Waldman WJ. Inhibition of respiratory syncytial virus in vitro and in vivo by the immunosuppre-ssive agent leflunomide[J]. Antivir Ther, 2011, 16(3): 309-317. doi: 10.3851/IMP1763 [21] Sepúlveda CS, García CC, Damonte EB. Antiviral activity of A771726, the active metabolite of leflunomide, against Junín virus[J]. J Med Virol, 2018, 90(5): 819-827. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25024 [22] Maghzi AH, Houtchens MK, Preziosa P, et al. COVID -19 in teriflunomide-treated patients with multiple sclerosis[J]. J Neurol, 2020, 267(10): 2790-2796. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09944-8 [23] Leca N. Leflunomide use in renal transplantation[J]. Curr Opin Organ Transplant, 2009, 14(4): 370-374. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32832dbc48 [24] Morita S, Shinoda K, Tamaki S, et al. Successful low-dose leflunomide treatment for ganciclovir-resistant Cytomegalovirus infection with high-level antigenemia in a kidney transplant: a case report and literature review[J]. J Clin Virol, 2016, 82: 133-138. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2016.07.015 [25] Di Maira T, Little EC, Berenguer M. Immunosuppression in liver transplant[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 2020, 46-47: 101681. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2020.101681 [26] 傅元凤. 霉酚酸酯治疗肾小球疾病的探讨[D]. 广州: 南方医科大学, 2008. Fu YF. The study of mycophenolate mofetil therapy for nephrotic disease[D]. Guangzhou: Southern Medical University, 2008. [27] Hirunsatitpron P, Hanprasertpong N, Noppakun K, et al. Mycophenolic acid and cancer risk in solid organ transplant recipients: systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2022, 88(2): 476-489. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14979 [28] Chang QY, Guo FC, Li XR, et al. The IMPDH inhibitors, ribavirin and mycophenolic acid, inhibit peste des petits ruminants virus infection[J]. Vet Res Commun, 2018, 42(4): 309-313. doi: 10.1007/s11259-018-9733-1 [29] Kato F, Matsuyama S, Kawase M, et al. Antiviral activities of mycophenolic acid and IMD-0354 against SARS-CoV-2[J]. Microbiol Immunol, 2020, 64(9): 635-639. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12828 [30] Wang YN, Li PF, Lavrijsen M, et al. Immunosuppressants exert differential effects on pan-coronavirus infection and distinct combinatory antiviral activity with molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir[J]. United European Gastroenterol J, 2023, 11(5): 431-447. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12417 [31] Sebastian L, Madhusudana SN, Ravi V, et al. Mycophenolic acid inhibits replication of Japanese encephalitis virus[J]. Chemotherapy, 2011, 57(1): 56-61. doi: 10.1159/000321483 [32] Chiem K, Nogales A, Lorenzo M, et al. Identification of in vitro inhibitors of monkeypox replication[J]. Microbiol Spectr, 2023, 11(4): e0474522. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.04745-22 [33] Yin YB, Wang YJ, Dang W, et al. Mycophenolic acid potently inhibits rotavirus infection with a high barrier to resistance development[J]. Antiviral Res, 2016, 133: 41-49. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.07.017 [34] Sugimoto A, Watanabe T, Matsuoka K, et al. Growth transformation of B cells by Epstein-Barr virus requires IMPDH2 induction and nucleolar hypertrophy[J]. Microbiol Spectr, 2023, 11(4): e0044023. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00440-23 [35] Takhampunya R, Ubol S, Houng HS, et al. Inhibition of dengue virus replication by mycophenolic acid and ribavirin[J]. J Gen Virol, 2006, 87(Pt 7): 1947-1952. [36] 黄润业, 亓兰达, 陈国参, 等. 免疫抑制剂霉酚酸的研究及产业化进展[J]. 微生物学报, 2021, 61(10): 3010-3025. Huang RY, Qi LD, Chen GC, et al. Research and industrialization progress of immunosuppressant mycophenolic acid[J]. Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 2021, 61(10): 3010-3025. [37] Camero M, Buonavoglia D, Lucente MS, et al. Enhancement of the antiviral activity against caprine herpesvirus type 1 of acyclovir in association with mizoribine[J]. Res Vet Sci, 2017, 111: 120-123. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2017.02.012 [38] Naka K, Ikeda M, Abe KI, et al. Mizoribine inhibits hepatitis C virus RNA replication: effect of combination with interferon-alpha[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2005, 330(3): 871-879. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.062 [39] Yanagida K, Baba C, Baba M. Inhibition of bovine viral dia-rrhea virus (BVDV) by mizoribine: synergistic effect of combination with interferon-alpha[J]. Antiviral Res, 2004, 64(3): 195-201. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2004.09.001 [40] Liu JS, Zhang K, Ji Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of mizoribine treatment in nephrotic syndrome complicated with hepatitis B virus infection: a clinical study[J]. Ren Fail, 2016, 38(5): 723-727. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2016.1158035 [41] Pancheva S, Dundarova D, Remichkova M. Potentiating effect of mizoribine on the anti-herpes virus activity of acyclovir[J]. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci, 2002, 57(9-10): 902-904. doi: 10.1515/znc-2002-9-1024 [42] Yuan X, Chen C, Zheng Y, et al. Conversion from mycophenolates to mizoribine is associated with lower BK virus load in kidney transplant recipients: a prospective study[J]. Transplant Proc, 2018, 50(10): 3356-3360. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.01.059 [43] Akioka K, Ishikawa T, Osaka M, et al. Hyperuricemia and acute renal failure in renal transplant recipients treated with high-dose mizoribine[J]. Transplant Proc, 2017, 49(1): 73-77. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.11.015 [44] Shi Y, Liu H, Chen XG, et al. Efficacy and safety of mizori-bine combined with tacrolimus in living donor kidney transplant recipients: 3-year results by a Chinese single center study[J]. Transplant Proc, 2019, 51(5): 1337-1342. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.03.014 [45] Tan JLC, Wong E, Bajel A, et al. Severity of mucositis du-ring allogeneic transplantation impacts post-transplant cyclosporin absorption[J]. Bone Marrow Transplant, 2020, 55(9): 1857-1859. doi: 10.1038/s41409-020-0795-7 [46] Wang LL, Zeng GT, Li JQ, et al. Association of polymorphism of CYP3A4, ABCB1, ABCC2, ABCG2, NFKB1, POR, and PXR with the concentration of cyclosporin A in allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients[J]. Xenobiotica, 2021, 51(7): 852-858. doi: 10.1080/00498254.2021.1928791 [47] Akiyama H, Yoshinaga H, Tanaka T, et al. Effects of cyclosporin A on hepatitis C virus infection in bone marrow transplant patients. Bone Marrow Transplantation Team[J]. Bone Marrow Transplant, 1997, 20(11): 993-995. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700996 [48] Liu DD, Ndongwe TP, Ji J, et al. Mechanisms of action of the host-targeting agent cyclosporin a and direct-acting antiviral agents against hepatitis C virus[J]. Viruses, 2023, 15(4): 981. doi: 10.3390/v15040981 [49] Qing M, Yang F, Zhang B, et al. Cyclosporine inhibits flavivirus replication through blocking the interaction between host cyclophilins and viral NS5 protein[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2009, 53(8): 3226-3235. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00189-09 [50] Sauerhering L, Kupke A, Meier L, et al. Cyclophilin inhibitors restrict Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus via interferon-λ in vitro and in mice[J]. Eur Respir J, 2020, 56(5): 1901826. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01826-2019 [51] Sauerhering L, Kuznetsova I, Kupke A, et al. Cyclosporin a reveals potent antiviral effects in preclinical models of SARS-CoV-2 infection[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2022, 205(8): 964-968. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202108-1830LE [52] 田璐, 刘文军, 孙蕾. 亲环素A对冠状病毒复制的影响及其抑制剂的抗病毒作用研究进展[J]. 生物工程学报, 2020, 36(4): 605-611. Tian L, Liu WJ, Sun L. Role of cyclophilin A during coronavirus replication and the antiviral activities of its inhibitors[J]. Chinese Journal of Biotechnology, 2020, 36(4): 605-611. [53] Glowacka P, Rudnicka L, Warszawik-Hendzel O, et al. The antiviral properties of cyclosporine. focus on coronavirus, he-patitis C virus, influenza virus, and human immunodeficiency virus infections[J]. Biology (Basel), 2020, 9(8): 192. [54] Mamatis JE, Pellizzari-Delano IE, Gallardo-Flores CE, et al. Emerging roles of cyclophilin a in regulating viral cloaking[J]. Front Microbiol, 2022, 13: 828078. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.828078 [55] Yang M, Xu ZX, Yan HL, et al. PD-L1 cellular nanovesicles carrying rapamycin inhibit alloimmune responses in transplantation[J]. Biomater Sci, 2021, 9(4): 1246-1255. doi: 10.1039/D0BM01798A [56] Hoff U, Markmann D, Thurn-Valassina D, et al. The mTOR inhibitor rapamycin protects from premature cellular senescence early after experimental kidney transplantation[J]. PLoS One, 2022, 17(4): e0266319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266319 [57] Benedetti F, Sorrenti V, Buriani A, et al. Resveratrol, rapamycin and metformin as modulators of antiviral pathways[J]. Viruses, 2020, 12(12): 1458. doi: 10.3390/v12121458 [58] Wang RF, Zhu YX, Zhao JC, et al. Autophagy promotes replication of influenza A virus in vitro[J]. J Virol, 2019, 93(4): e01984-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01984-18 [59] Saso W, Tsukuda S, Ohashi H, et al. A new strategy to identify hepatitis B virus entry inhibitors by AlphaScreen technology targeting the envelope-receptor interaction[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2018, 501(2): 374-379. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.04.187 [60] Adamson AL, Le BT, Siedenburg BD. Inhibition of mTORC1 inhibits lytic replication of Epstein-Barr virus in a cell-type specific manner[J]. Virol J, 2014, 11: 110. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-110 [61] Needham J, Adamson AL. BZLF1 transcript variants in Epstein-Barr virus-positive epithelial cell lines[J]. Virus Genes, 2019, 55(6): 779-785. doi: 10.1007/s11262-019-01705-8 [62] Heredia A, Gilliam B, Latinovic O, et al. Rapamycin reduces CCR5 density levels on CD4+T cells, and this effect results in potentiation of enfuvirtide (T-20) against R5 strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in vitro[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2007, 51(7): 2489-2496. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01602-06 [63] Heredia A, Latinovic O, Gallo RC, et al. Reduction of CCR5 with low-dose rapamycin enhances the antiviral activity of vicriviroc against both sensitive and drug-resistant HIV-1[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2008, 105(51): 20476-20481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810843106 [64] Latinovic OS, Neal LM, Tagaya Y, et al. Suppression of active HIV-1 infection in CD34+ hematopoietic humanized NSG mice by a combination of combined antiretroviral therapy and CCR5 targeting drugs[J]. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses, 2019, 35(8): 718-728. doi: 10.1089/aid.2018.0305 [65] Weichseldorfer M, Affram Y, Heredia A, et al. Anti-HIV activity of standard combined antiretroviral therapy in primary cells is intensified by CCR5-targeting drugs[J]. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses, 2020, 36(10): 835-841. doi: 10.1089/aid.2020.0064 [66] Martin AR, Pollack RA, Capoferri A, et al. Rapamycin-media- ted mTOR inhibition uncouples HIV-1 latency reversal from cytokine-associated toxicity[J]. J Clin Invest, 2017, 127(2): 651-656. doi: 10.1172/JCI89552 [67] Husain A, Byrareddy SN. Rapamycin as a potential repurpose drug candidate for the treatment of COVID-19[J]. Chem Biol Interact, 2020, 331: 109282. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2020.109282 [68] 厚玉姣. 6-硫鸟嘌呤治疗儿童急性淋巴细胞白血病疗效及安全性的系统评价[D]. 兰州: 兰州大学, 2016. Hou YJ. Efficacy and safety of 6-thioguanine for childhood ALL: a systematic review[D]. Lanzhou: Lanzhou University, 2016. [69] Yin YB, Chen SR, Hakim MS, et al. 6-Thioguanine inhibits rotavirus replication through suppression of Rac1 GDP/GTP cycling[J]. Antiviral Res, 2018, 156: 92-101. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.06.011 [70] Chen DY, Liu Y, Zhang F, et al. 6-Thioguanine inhibits herpes simplex virus 1 infection of eyes[J]. Microbiol Spectr, 2021, 9(3): e0064621. doi: 10.1128/Spectrum.00646-21 [71] Pringle ES, Duguay BA, Bui-Marinos MP, et al. Thiopurines inhibit coronavirus spike protein processing and incorporation into progeny virions[J]. PLoS Pathog, 2022, 18(9): e1010832. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010832 [72] Slaine PD, Kleer M, Duguay BA, et al. Thiopurines activate an antiviral unfolded protein response that blocks influenza A virus glycoprotein accumulation[J]. J Virol, 2021, 95(11): e00453-21. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00453-21

下载:

下载: